“Lift ev’ry voice and sing,

‘Til earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty…

facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on ’til victory is won.”

Often called the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” was written as a poem by NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson, whose brother set the poem to music.

Lifting Up My Voice

I cannot even remember a time that I did not lift up my voice and sing songs of faith, songs of hope. I have always used my voice to speak out about injustice.

I cannot even remember a time that I did not lift up my voice and sing songs of faith, songs of hope. I have always used my voice to speak out about injustice.

As a family, when we were children, we spent summers in Broussard, Louisiana with our grandparents, great grandparents, and our extended family. Both of our parents were born and raised in Broussard and lived only a few houses away from each other.

I remember my brother David, who was always falling and injuring himself. David fell while we were on vacation in Broussard which caused an injury to his arm. As the arm was getting more and more swollen, my great grandmother, Virginia Pellerin, insisted that to stop the infection all that was needed was white string! As my brother sobbed, my great grandmother proceeded to stop the infection by tying the string to my brother’s fingers and his toes!

No one in the family ever questioned Virginia Pellerin because she was the matriarch, and a no nonsense, formidable woman. If she said David could be cured, even if the adults thought the notion was ridiculous, they did not dare say anything.

My poor, embarrassed, brother just kept crying. I was about 12 years old, and I spoke up. I insisted, in my 12-year-old indignation, that it was not possible for string to work! The adults in the room just stared at me as if to say without words: “Shut up Melinda!” I did not stop! I thought I was taking a stand for my brother and that stand cost me! I got into trouble with my Dad. It was as John Lewis, the esteemed Civil Rights leader who died recently might have called “Good Trouble!

God of Our Silent Tears

I am who I am because of my ancestors. I am who I am through their silent tears, their acts of steadfast resistance and faith. I am who I am because I stand on their shoulders and they have grounded me to act for what is right, for what is just. I lift my voice and sing. I understand their tears, their lives as African Americans in this country. It is through their silent tears that I am strong.

In her article entitled “You Want a Confederate Monument? My Body Is a Confederate Monument” Caroline Randall Williams makes the point that “The black people I come from were owned and raped by the white people I come from. Who dares to tell me to celebrate them?” Further, Williams states that “I have rape-colored skin. My light-brown-blackness is a living testament to the rules, the practices. …of the Old South.”

My grandmother, on my mother’s side, Adrienne Frances-Melancon, had a father who was a white. And no, Adrienne’s mother, my great grandmother, was not married to this white man,but this white man held all the power. He held white power. The Frances family was well known, and Mr. Frances had white privilege!

At four or five years of age my great grandmother placed her young daughter, Adrienne, in her white father’s hands. My grandmother was put to work in her white father’s house. My grandmother would tell me stories that she was taunted by her white siblings. Adrienne was told: “You better never ever claim our daddy as yours, you’re a (the N Word)! You’re ugly, you’re black! “But my grandmother was stronger than all the insults, stronger than the difficult work she as a mere child had to endure. In her sheer determination, Adrienne survived.

Adrienne and Virginia, my grandmother and great grandmother, had no education and neither woman could read or write their own names; yet these are the women who stand with me, whom I admire as women of courage. They were scholars; they were my teachers, my mentors, and the models. I turn to models I hope I always emulate. My strength, my faith comes from them.

I remember bringing baskets of food with my grandmother Adrienne to people in need. My great grandmother, Virginia, told us all about our ancestors and of one who hanged herself in defiance of her slave master. My ancestor was a house slave who worked on a plantation in the South. My great grandmother told the story that this slave’s master was cruel and that any time she did something he perceived to be wrong, she was beaten. She was warned that if she made one more mistake in the “big house” she would get severely beaten as her punishment.

She was cleaning in the dining room and broke the handle of a china cup. She understood the violent beating that awaited her, so she made a decision to die on her own terms. According to my great grandmother, my ancestor found a rope, tied it around her neck, and hanged herself.

When the master found out he was enraged. The master called out all the slaves he owned to the site where her body was hanging and told them that her body would hang there until the buzzards came. She would not have a Christian burial. “Let the buzzards eat the body!” the master proclaimed. This would be an example to other slaves. At night the master’s son, who had been raised by my ancestor, took slaves with him and cut her body down and buried her in an unmarked grave.

I have the color of rape too, inside of me, the DNA of women who were discounted and abused in the practices of violence in the south. And here I am, their descendant.

Singing Out for Just Causes: My Ancestors with Me Today

When we were visiting Broussard during a family trip, I went with my grandmother Adrienne into town. My grandmother walked into one store and I spotted a bench in front of a beauty salon that my grandmother said was a “white” salon. I was very young but noticed something very strange about the bench in front of the salon. It had the words: “White Only.” I sat down. I knew then that there was something wrong about the sign. It made me angry.

My grandmother came running out of the store, screaming at me to get up. I folded my arms and ignored her; I was not leaving that bench! In frustration grandmother left me there. No one else came by. After a while I got up and left. My first protest!

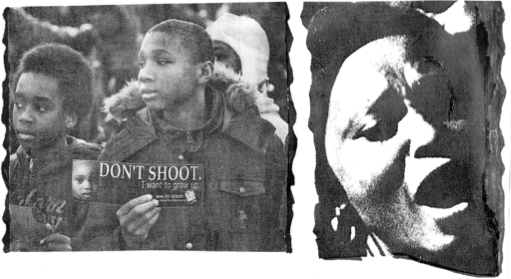

These are the memories as an African American woman I am aware of and was carrying when I spoke against the lack of transparency and the violence in the Springfield Police Department. I spoke to these issues even while the police officers were standing nearby at a rally several years ago.

Adrienne and Virginia were with me during these confrontations. These women are the women I remember when I’ve called for political officials to act like they are working for the people who put them in office; when I taught my middle school students to stand up for justice and speak out; when I write articles and when I have been questioned about my participation in peaceful protests, I lift my voice up. I continue to sing out for just causes and I will never back down.

What Can the Dark Past Teach White People?

“Lift Every Voice and Sing” is more than the Black National Anthem. It is a history of a people, the struggles of a people and their resilience. Through the ugliness of slavery, Jim Crow, segregation, and the racism of these pandemic times, that we are here.

We are still fighting. There are those who say: “I don’t see race as an issue. BLM is a terrorist group; they are communists, socialists, against family values.” These are all lies, distortions of a truth that America does not want to deal with.

“We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered out of the gloomy past til now we stand at last where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.” We continue to sing “our” song. We matter. The lessons we all can learn from my ancestors, from the legacy, the history of your sister and brothers is that we need to be willing to listen, to march to victory, and place our faith in God.

In the Gospel of John, chapter 3, Jesus meets the woman at the well. Samaritan Lives Mattered, Black Lives Matter. The woman at the well is the outsider, she is not like the other women in the village. She has been ostracized; she is culturally different but that does not matter to Jesus, the Jewish Rabbi at the well. The Samaritan Woman’s life mattered. SLM. Relationship matters to Jesus.

The Gospel can teach us all about radical racial reconciliation and how transformative this meeting at the well was for the Samaritan woman in the first century and for the world in the twenty-first century! It will take a meeting at the sacred, 21st century well. Like Jesus and the woman, we must be willing to meet the other, the disenfranchised, our brothers and sisters, in dialogue, with honesty, courage, respect and openness.

Those in power, the oppressors, must be willing to listen as Jesus did. The road towards justice, as the song’s lyrics highlight, is stony. The Gospel tells us that the road towards reconciliation is a “stony road”; the encounter with the other, the dear neighbor, has transformative power. The Samaritan woman was able to place her water jug down and spread the Good News. The road to the well does not have to remain stony. Reconciliation begins when we speak to each other.

This reconciliation road is fraught with many obstacles, many stones, but in all things may we forever stand true to our God. Protest injustice. Lift our voices up. We have so much work to do which begins when we lift our heavy water jugs laden with stereotypes, white privilege, racism, hate and prejudice. Jesus sees the Samaritan woman and without judging her, he asks her for water.

John’s Gospel can also teach us that dialogue and honesty cannot stay at the well. After placing our water jugs down, we need to act, to speak out, to pray, to become anti-racist and lift up our voices, to “open [our] eyes and forever stand true.”

The truth will set us free and it is not easy to acknowledge when oppression is so powerful, so insidious. Oppressors, those in power, will always be ready to tell a false narrative about the people who fight for justice, to “weaponize” a movement.

Then, there is racism in the Catholic Church that has to be confronted. We as Catholics need to go into church and knock the tables down. We have to just do it, and if the hierarchy doesn’t like it, well, too bad. We just have to get used to knocking those tables down.

Whenever the road seems to be too difficult for me, whenever the fight seems to be just too exhausting, I go to gospel songs. I go to my memories of those whose shoulders I stand on: “Facing the rising sun of our new day begun, let us march on ’til victory is won.”

Sr. Melinda Pellerin, ssj, is a vowed member of the Sisters of Saint Joseph, a board member of the National Black Sisters’ Conference, and a Pastoral Minister at Holy Name Parish in Springfield, MA. She lectures on African American History, Black Catholics in the church, and Black Lives Matter.