by Brenna Cussen-Anglada

The farm I live on in community at St. Isadore Catholic Worker, where towns and the surrounding cities are on the ancestral and traditional lands of the Meskwaki and Ho Chunk from which they were forcibly removed after the land was stolen by White colonizers.

The farm I live on in community at St. Isadore Catholic Worker, where towns and the surrounding cities are on the ancestral and traditional lands of the Meskwaki and Ho Chunk from which they were forcibly removed after the land was stolen by White colonizers.

We Christians don’t have a great track record when speaking about the environment in the light of faith. The story we have been told and most of us have unconsciously embraced and perpetuated, is that humans are separate from creation. At best, we see ourselves as tasked with “stewarding” creation. At worst, creation is something we can exploit and use for our benefit. Most of us lie somewhere in the middle of that spectrum, no matter how we wish to be good stewards.

A friend of mine who had studied theology at Notre Dame and deeply cared about Catholic Social Teaching and who had prepared for years to be a priest, did not know of the Church’s rich tradition of love for Creation. What if we, our Church, our communities, told our TRUE story?

Our oldest written scripture says that the first person, adam, was made out of the adamah, (which means earth/soil in Hebrew). We are made from the same soil that gives rise to all life. What if we shared this story, and lived as though it were true?

What if we had inscribed onto our hearts the story of when the Cedar trees, in the Book of Isaiah, revolt against the king of Babylon, declaring, “Since you have been laid low, no one comes to cut US down!” (Is 14:8).

What if we looked to the birds of the air, or the wildflowers, as Jesus tells us to, as role models for how to be in right relationship with God? What if we really and truly respected these flowers and these birds as our teachers?

Part of our story is our liturgical calendar which in the northern hemisphere at least, lines up with the calendar of the unfolding seasons. At St. Isidore, we try to celebrate both, so that we can know that Christmas and Winter Solstice mark the coming of the Light. As we celebrate the Spring Equinox and the Feast of the Annunciation, we recognize, like Mary did, that the “world is about to turn.” As we honor the dead in November, on All Saints and all Souls, we watch the leaves fall and plants die back.

At our Catholic Worker Farm we try to reclaim these holy, sacred cycles of the year and to learn the stories and traditions of the Indigenous peoples on whose land we live now–how they were removed, how they survived.

Colonization was as deliberate process to wipe out memories of culture, languages, traditions. We inherited the legacy of Whiteness and the privileges it offers; we chose to forget our histories, traditions, and stories, trading them for economic and social status. Others racialized as Black, Indigenous, Latino, Asian, had their traditions stolen from them, though many resisted, and found ways to hold onto them, or recover them.

In their new book, Healing Haunted Histories, Elaine Enns and Ched Meyers talk about how embracing “Whiteness” has required a disturbing “unknowing,” a complete wiping out not only of our own ancestral histories, but also a refusal to understand the traditions of the peoples of this land, or to know the history of genocide and forced removal that took place here.

They write: “If we wish to ‘reinhabit’ the watersheds in which we reside, and forge respectful and restorative relationships with Native neighbors, we will have to abandon the privileges inherent in settler ‘unknowing’ and embrace a double task. First, we will need to build our literacy in Indigenous histories held by the land and peoples around us, as well as their continuing culture and lifeways. Second, we will need to revise our own narratives, which for so long have been distorted by colonial supremacy.”

I have traveled North several times over the winter, where Indigenous women are leading at least five different camps that stand in opposition to Enbridge Energy’s new Line 3 construction which crosses treaty territory land which rightfully belongs to the Anishinaabe with their Wild Rice beds, sacred to their people for at least 15,000 years, which are being destroyed. For the Anishinaabe, land is not separate from themselves. Destroying the land, these wild rice beds, is a direct attack on their culture, their way of life, their people.

In a chapter in the book “Buffalo Shout, Salmon Cry, “Jennifer Harvey points out that “the belief systems that led settler peoples to wreak havoc on the environment were and are the same ones that enabled the displacement of Native peoples. To treat the land as commodity required viewing the people of that land similarly; ecocide and genocide go hand in hand. It is no accident, for example, that wherever pipeline projects go through Native communities, there is an epidemic of Native women and girls who go missing and murdered.”

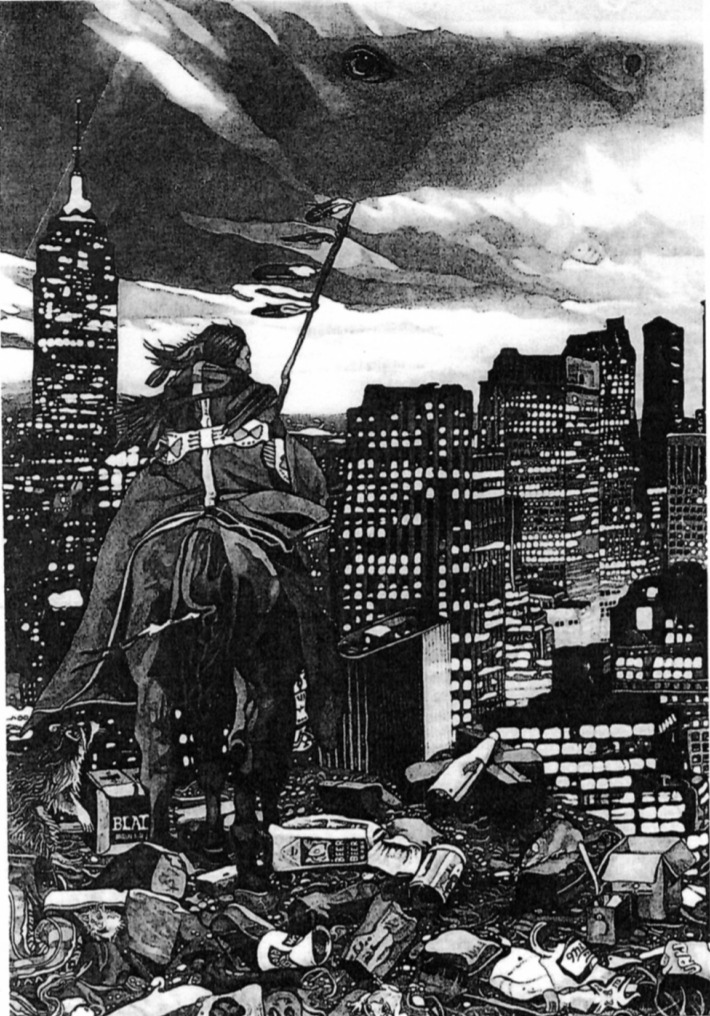

This is not our land; instead, we are part of the community of settlers who have perpetuated both ecocide and genocide. Work we do on behalf of “the environment,” must be done out of respect for, and listening to, Indigenous voices, under Indigenous leadership.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of Braiding Sweetgrass, writes that for restoration, we need “re-story-ation,” stories of the specific Indigenous people on whose land we live. It will take years of work, to recover these stories and to make them a part of ourselves. It will be worth it.

Brenna is a life-time Catholic Worker and a close friend and inspiration to members of Agape.