Armed only with banners advocating mercy, and signs decrying the death penalty, nonviolent peacemakers from Agape, Pax Christi, Veterans for Peace and elsewhere, regularly stand vigil in front of the John Joseph Moakley Courthouse in Boston. In the early morning, a stream of employees, visitors, victims and lawyers pass before us, some with averted eyes or unreadable expressions, some clearly disdainful, like the man who muttered, “We should fry him – crisp as bacon.” Others, perhaps reflecting the general distaste for the death penalty in Massachusetts, pause to read the banners, or quietly voice appreciation and thanks for our witness. Reporters from the major news outlets are strategically stationed in view of the entryway, eager to capture the highlights of the day. On several occasions, interviews of vigil participants takes place, the reflections broadcast beyond our small witness.

As I write, the federal capital trial of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, admitted and convicted Marathon Bomber, is in its winding-down phase as the defense team offers a mosaic of reasons why this young man should be spared the death penalty, despite his culpability. During these latter weeks, family members, teachers and others brought in to testify, recall the young person they once knew, describing him as friendly, gentle and intelligent – not the kind of kid prone to violent behavior. Clearly, the defense team hopes to soften the perception of him as a categorically evil monster, beyond redemption. Focusing on the influence of his turbulent family background and Dzhokhar’s idolized yet controlling older brother Tamerlan, a former brother-in-law said that in Chechen culture, he would be “obligated to do what his older brother tells him,” and that it was “better to be a dog than a younger brother.”

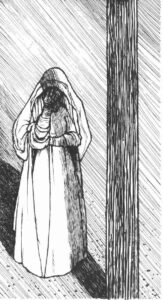

Through graphic testimony and visuals presented by the prosecution, the trial has laid bare the still raw suffering of the families of those brutality killed, and has exposed the enduring pain of the forever wounded. Amidst the repetitive and dire picture of destruction, the abyss of pain generates little empathy in many hearts for the young man on trial for his life. Flanked on both sides by the women of the defense team, Dzhokhar’s impossible aloneness seems somewhat mitigated by their mindfulness. Their simple gestures of human contact and solace remind us that, despite the radical fact of sin, individual and social, ”each person’s human dignity must be honored” as it is imparted by an unconditionally loving God, not by us.

As the trial evolves, Dzhokhar, the victims, jurors, and the people of Boston are required to confront the madness that exploded into havoc on a bright, celebratory spring day in 2013. That day – burned into memory’s horror chamber – was one in which few in Massachusetts were spared the experience of fear and outrage that pervaded the very atmosphere of the city as the blasphemy of destruction screamed its way into our small world. Out of the blue – here, not there – not Iraq or Afghanistan, not Syria or Nigeria or Yemen – terror came calling, ripping from us the naive innocence that had led many to believe that we, the righteous of American, are somehow immune to the kind of violence that is daily fare in other parts of the world. All of us traumatized, it was difficult at that time to consider the possibility that the global “culture of death,” in which our country and its military are implicated, could spawn a response of malevolence directed toward innocent people in our city, fulfilling the prophesy that violence begets violence, ad infinitum.

Two years later, a collectively wounded psyche, evoked by the stories of the wounded, gropes its way toward resolution, seeking meaning and healing. The prosecution, pursuing “justice” for the federal government, argues that the extent of the carnage requires the prescription of death to insure some deliverance from the trauma of the tragedy; the jurors, all selected with the caveat that they had to consider the option of execution if Dzhokhar was found guilty on charges qualifying for death, listen to final evidence. After convicting him on all charges (17 of which qualify for death), they prepare to decide his fate. And the defense, opposed to execution, offers the only other option available -that of imprisonment without end – inevitably sealing his tomb in another way because of the cruel limitations imposed by a penal system built on retributive rather than rehabilitative principles.

In Kevin Cullen’s column of April 28 in the Globe, David Bruck, speaking for the defense, spared no punches when he described the likelihood of Dzhokhar’s imprisonment in the supermax prison in Colorado if death is avoided. “One punishment is over quickly…the other will last for years and decades while he is locked away and forgotten. No more spotlight like the death penalty brings…And no martyrdom. Just years and years of punishment, day after day, while he grows up to face the lonely struggle of dealing with what he did.”

Mr. Bruck’s conclusions are not hyperbolic. Currently, the United States Penitentiary Maximum prison (ADX) is the only federal super-max prison in the United States, housing 490 male inmates who spend a minimum of 12 months in solitary confinement (22 – 24 hours/day) before consideration is given for less time. In reality, Amnesty International cites a report stating that the average length of time before an inmate receives some reprieve from the torture of killing isolation is 8.2 years, amounting to “cruel, inhuman treatment…in violation of international law.”

Juan Mendez, Special Rapporteur on Torture for the United Nations, has tried for years to gain access to Guantanamo, the ADX and other high profile prisons in the United States, without success. Laura Roverner, a legal expert on prison conditions from the University of Denver says, “The fact that he (Mendez) hasn’t received response is contemptible”…”It puts the US in the company of countries like Syria, Pakistan and Russia that also have been unresponsive to requests for country visits.” According to the ACLU, on any given day 80,000 people in the US are held in solitary. Mendez says, “The numbers are staggering, but even worse is the length of terms…it is not uncommon for people to spend 25, 30 years or even more in solitary confinement.” Some people, citing the severity of life in such an institution favor this as an even more suitable punishment. However, those concerned with a failed prison system, lament the miserable trade-off of substituting life without parole in such a place for the death penalty, citing the poverty of imagination and meanness of spirit necessary to create and maintain hell’s anteroom here on earth.

More than three months have passed since Agape and Pax Christi MA initiated an effort to address the federal government’s pursuit of the death penalty. Initially, one of our hopes was to gain the support of the leadership of the Catholic Church. On February 4, our letter to Cardinal Sean O’Malley asked that he reiterate his (and our Church’s) condemnation of the death penalty and apply it specifically to the trial happening in our own neighborhood. Following this, we delivered a statement, accompanied by 400 personal endorsements.

On Easter Monday, “A Statement of the Roman Catholic Bishops of Massachusetts on the Death Penalty” was issued by the Cardinal’s office, and included the names of the bishops of the other dioceses. Recently, we were told that the Cardinal appreciates our witness, though no clergy has yet joined us. However, we persist in the hope of further dialogue on this issue, and on other crucial concerns that beg our witness. As Franz Jagerstatter, martyred for his refusal to serve Hitler said: “If the Church stays silent in the face of what is happening, what difference would it make if no church were ever opened again.”

The days of vigil have provided rich opportunities for reflection, and it becomes apparent that this one case illuminates the network of connections among the myriad manifestations of individual and state-sponsored violence that runs like a toxic current among us, contaminating us all. How can we, after all, talk about this example of calculated destruction without being reminded of the surging unrest that abides in the hearts of the chronically dispossessed and brutalized – a combination of injustices fraught with dire implications? How can we not think of the 50 million refugees from war and civil unrest who flee their homelands and arrive in other beleaguered nations, bereft of resources to begin new lives? How can we not realize that massive militarism and never-ending wars, the dispatch of drones, racism and the mass incarceration of people in the US is a mix of ingredients brewing cataclysmic acts and perpetual suffering? It is time to wake up.

On May 11, the defense brought to the witness stand, Sr. Helen Prejean, Catholic nun and activist icon of the anti-death penalty movement. As spiritual guide, this woman of deep condition and extravagant compassion, has, over 20 years, accompanied six “dead men walking” to their deaths, at the same time working with families of murder victims, both commitments crucial to her ministry of mercy. She says: “The important thing is that when you come to understand something you act on it, no matter how small that act is. Eventually, it will take you where you need to go” This “need” brought her to Dzhokhar’s prison cell where she spoke with him on five different occasions. Though hobbled in the range of her testimony, she communicated his words to the jury: “No one deserves to suffer the way they did.” Whether these are perceived as an indication of remorse remains to be seen. We can only trust that a single juror among the twelve thwarts the demand for death, perhaps trusting in the possibility of eventual healing for the victims – and the perpetrator – without the final solution of execution.

And so we stand, praying to discern the ways and means of “mercy” as in “Blessed are the merciful” believing that mercy and love ultimately seed the fruit of justice, and that it is worth spending our life’s time figuring out how to do and be mercy. We continue to insist that Dzhokhar’s life be spared and that it is past time for the United States to eliminate the use of the death penalty for even the most egregious criminals: not one more execution, whether by lethal injection, high-voltage electricity, gas, bullets, or a rope around the neck – no more “dead men walking.” None of this barbaric behavior adds a single bit of life or the tiniest bit of grace to a world well-versed in death. It cannot be of God or blessed by the gospel or person of the nonviolent Jesus Christ. “Enough,” we say.

Somber and sad, we hear the jury’s pronouncement of death for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, and mourn again the tragedy of lives lost, and souls and bodies maimed by human initiated violence.

Though our standing and our stance for Tsarnaev’s final sentencing by Judge O’Toole on June 24th at the Moakley Courthouse may bring few immediate results, it remains incumbent upon us as witnesses to the gospel of peace to utter words that may one day take wing and settle in others’ hearts. For now, we ask for the courage and strength to labor in love to end the death penalty, and to blanket the pain of the world with mercy. So be it.

Pat Ferrone has been an integral part of the life of Agape since its inception in 1982; in addition, Pat is the Regional coordinator of Pax Christi MA and a leader in the Peace and Justice Committee at St. Susanna’s parish in Dedham, MA.