For over 25 years, Agape has co-sponsored Stations of the Nonviolent Cross, in front of Boston’s State House, with a strong emphasis on the Death Penalty, which Jesus suffered and about which he spoke eloquently: “Do Not Kill”

As the jury selection and trial of Dzhokar Tsarnaev is in full gear, Agape and Pax Christi are sending a letter to Boston’s Cardinal O’Malley, to take a prophetic and vocal stand against the Death Penalty, even as we prepare for our own witness of prayer, fasting and public vigil. For more information, contact Agape by phone or email.

Who Can Disarm and Heal Dzhokhar by Brayton Shanley

Huffington Post

Having been a one-time marathoner, a fan of the Boston marathon, and finish line spectator, I was in shock by reports of the two bombs going off at the 2:50 mark at this same finish-line. My disbelief gradually evolved into angry thoughts at those who made and ignited the bombs. I have never felt such outrage at any mass murder. I was additionally enraged because Boston is a “home” for me. I know Boston’s streets well, especially Boylston Street, since I arrived in the fall of 1965 as a college freshman and lived around the corner. When I tried to grasp that the Marathon had been bombed, my mind froze and began to seethe in disbelief.

We know now a lot more about who bombed the finish line and, sordidly, why. But what is of eternal concern for me, is how state officials and police, respond to dangerous homicidal people once the murderous deed is done and how different their response usually is from treating murder with nonviolent means. In nonviolent theory and practice there is singular intent on employing skilled tactics that limit further violent escalation and harm. Sadly, state officials and police are not trained to practice methods that de-escalate violence, especially in crises that are life-threatening.

So, I wonder how the gospel of nonviolence would teach us to deal with perpetrators of mass murder when they are still at large. The state, with governors and police force, kicks into immediate high gear not with “why” something happens, so much as “that it happened” and to protect the public by finding, arresting or killing the dangerous criminal. This may seem fair and sensible while the suspects are on the run. Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev bombed the Marathon that killed three and maimed hundreds, and later, killed an MIT policeman, ending their killing spree with an action thriller-like fight-to -the death shoot-out with police in which Tamerlan, the older brother, was killed. Dzhokhar, a nineteen year old, drove off, ditched the car-jacked vehicle in Watertown and ran. It is true that these homicidal men were running from their murders and should be considered “armed and extremely dangerous.”

However, if all we see is “armed and extremely dangerous,” then we are very likely to perpetuate the fatal flaw that we humans have been committing since the dawn of human conflict—fighting violence and viciousness with more violence and viciousness. A “my life or theirs” fear of murderers too often makes the murderer more desperate and dangerous; further, it convinces the police that killing the killer is the only “safe option.” A nonviolent intervention, on the other hand, is more likely to consider listening to all of the factors in the case, not just that they are pursuing monstrous killers on the run.

These factors include an important question

: Why did this happen? Krystle Campbell was one of the three victims who were killed. Her mother spoke at a press conference and was so grief-stricken that she could barely be heard. The most memorable phrase she could eke out in fragile, shaky words was “I just don’t understand.” Yes, we can all identify with that cry. She was saying, in essence: “This was senseless violence and now my daughter is dead. Why do I have to suffer losing the daughter I love so much to the insanity of murdering this beautiful innocent person?” Again, every sane, sensitive human, especially a parent, can relate deeply to her anguished feelings.

Men and Homicide

Nevertheless, if I ponder Krystle’s mother’s question:

“how could this happen?”–answers start to surface. The first clue of primary importance is that these brothers are male. Homicide is a male statistic: 90% of all homicides are committed by males. 62 mass murders have been committed throughout the US in the last 30 years; 61 have been perpetrated by men.

Why do males commit 90% of all murders? What are we teaching our boys? From Columbine on forward, these male shooters of all ages have been violent video game addicts. What is that steady drip of sadistic murder doing to their souls? Minds are bathed in the euphoria of killing other humans, even if the story line seems reasonable; good guys always kill bad guys. First reports of the personalities of the brothers depict them as full of machismo, both pumped with muscles and aggression. Older brother, Tamerlan boxed and the younger wrestled. Although wrestling seems benign next to boxing, both brothers seemed advanced at “dominate and defeat your opponent with violence” sports. There is no particular alarm here because the ethos of the popular culture around them condones the shooting violence-fantasy world of video games and awards men lavishly for their athletic prowess, however violent.

What kind of male role models influenced these brothers in the culture they were nurtured in as boys? Their father was very connected to his Chechen identity. He could easily have instilled rage in his boys at the Russian oppression of Chechnya and Vladimir Putin’s murderous crushing of the people’s revolution for independence. In 2002, 40 Chechen rebels took 850 hostages in a Moscow movie theatre. Russian forces pumped a poisonous gas into the theatre and attacked the rebels. 130 movie goers and the rebels were killed. These violent interactions are male perpetrated violence and revenge. Each side always assures itself that it is on the right side of history.

Psychologists who have been analyzing the brothers’ behavior have said that they both had indications of a confused ethnic and cultural identity. Am I Chechen, Islamic, or American? Psychologists in the field of adolescent male development, surmise that if young men are painfully confused about their true identity, many find a strong attraction to identify with the oppressed victim belief that the killer’s life has been ruined by someone else. The brothers’ mother strongly encouraged Tamerlan to practice Islamic faith, to keep him “out of trouble.”New reports suggest that the mother had recent, growing sympathies with radical Islam, began wearing a hijab and cited conspiracy theories that 9/11 was a US plot to make Americans hate Moslems. These impressionable immigrant boys are now relating to an identity of oppressed Muslims of ethnic Chechen origin, with simmering dislike of this country. This could be a volatile identity, with outlets of extreme violence by males as holy justice for the powerless.

President Obama is another male player in the equation. He was center stage in Boston two days after the marathon coverage. He came to offer presidential support and sympathy to a city in trauma and family members paralyzed with grief. As usual, his speechmaking is so easily delivered. It is tough and tender. He rallies Boston to stand tall. He reassures that we will find these cowards and bring them to justice. They will be sorry that they picked a tough town like Boston. He appears to be the Great Statesman at the crucible hour, delivering his words with a Black Baptist cadence and a convincing passion, an amazing moment of political oratory. Amazing too, how well most Presidential “Men” can compartmentalize the moment. In his job back in Washington DC, under the cover of “classified,” he signs off on drone bombings designed to kill “surgically” terrorists and jihadist enemy combatants throughout the Middle East. Although there are zero casualties on our side, drones often miss their mark and kill women, children and innocent men at weddings or in their own homes in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq. These acts of aggressive killing and injuring don’t rebound back from the Arab and Islamic world to us in any way? To see the whole picture of “why this happened” we had better think again.

In the practice of nonviolence, we begin with an echo of Jesus’ warning by saying that “all violence we send out, ricochets back. Send out hate and murder with our bullets and bombs and those bullets and bombs will someday reign down on us.” Obama travels to Colorado, Arizona, Newtown and now Boston, to comfort trauma victims of mass murder. His flaws as a comforter, while at the same time, the one who is responsible for killing innocents, are fatal. He is simply another man out there who models the problem of violence, not its resolution. The brothers from Cambridge could easily have been taking “my violence is good violence” cues from the many male authorities around them.

Can There Be Peaceful Negotiation?

The capture of Dzhokhar in Watertown was another telling moment. Unlike the shootout that killed Tamerlan, capturing Dzhokhar was an entirely different circumstance. I think it was potentially hopeful that those in charge of the case, from Mayor Menino to Governor Patrick, to the Police Chief of operations, were in favor of capturing him alive. The burning questions of “why he did it and who were his accomplices” would be definitively answered only if he were taken alive. However, these motives were not pure enough because they ignored crucial psychological and spiritual realities. These realities include the fact that, one more “killing the killer” strategy would succeed only in adding one more family in trauma, one more killing and in a city already overwhelmed with suffering and death.

If this nineteen year old were in a panic, to take his own life, this real life drama ends in his nihilistic sorrow of self destruction. An important nonviolent verity applies here: “Nothing ultimately good and hopeful can come from an act of violence. …ever.” Violence is a hopeless aggression that can only bring human beings suffering; in this case, turning SWAT teams into swift and efficient killers and forcing the hunted perpetrator into suicide.

Negotiation with the Fugitive

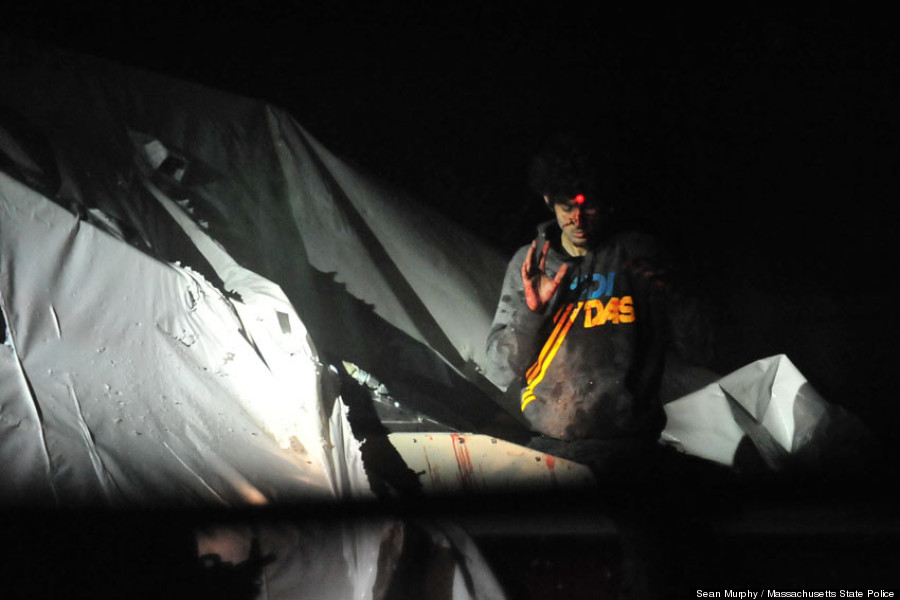

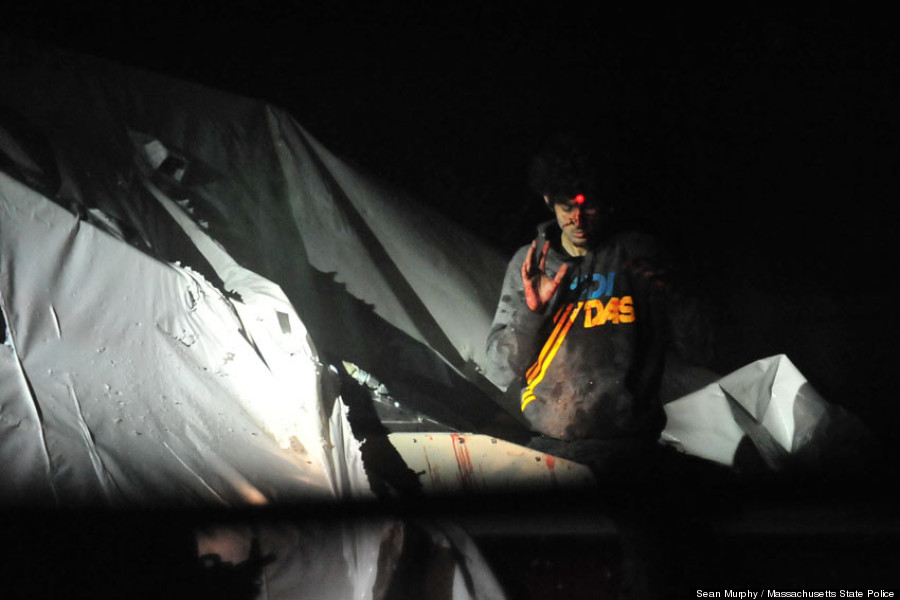

Having witnessed the efficacy of nonviolent conflict resolution, I continually puzzled over how the police could best direct the safe capture of Dzhokhar. The evidence shows that he was unarmed while hiding in the boat. Why then did the police close in with a show of force with what must have seemed like a 1,000 rounds of ammunition of police fire power? The only “words” of negotiation here came in the form of a deafening din of gunfire. The logic of the gun blasts? “Your only chance of survival is immediate and absolute surrender.” But, if you want to save the possibility of a more peaceful outcome with this armed perpetrator who doesn’t appear suicidal, it is most effectively carried out by someone experienced in nonviolent mediation. When he was captured, Dzhokhar had a throat wound. No real skill in that move, if the police shot him while they were closing in.

In listening to “police officials” live on the radio, as they moved in for the kill or capture, it was clear from interviews with police spokespersons that they would not put themselves at any risk to capture him. “It is much safer to just kill him if he appears at all dangerous” was the drift of what the police officials were saying as they got closer to Dzhokhar.

But what might a nonviolent negotiator bring to the moment? First would be compassion for the hellish prison of this fugitive, even if it was of his own making . And yes, he could be hair-trigger dangerous. In a crisis like this I think of a question I learned from the Buddhist tradition that unlocks the death trap of enemy hatred and fear. “Why is the enemy suffering?” Dzhokhar and his brother, Tamerlan, had just spent several days in the dark hell of inflicting suffering and death. As this kill or be killed drama came down to its final hours, their behavior became more murderous, ending in a bizarre shoot-out with police in Watertown, killing Tamerlan. This left Dzhokar all alone, wounded and surrounded by thousands of police.

Mother as Nonviolent Negotiator

How might a nonviolent negotiator prepare for this moment? He or she might approach Dzhokhar as would a parent of a teenager gone very wrong. A mother’s unconditional love for her son might make the best negotiator here. A woman with a mother’s touch can communicate with a compassionate tone. Were Dzhokhar armed and ready to defend himself, she could speak in a disarming way, using words of calm, reassuring concern. “Are you all right? Are you bleeding?” Disarming a teenage boy with the reassurance of a mother could immediately de-escalate the volatile tension of the crime scene and maximize the potential for the male not to take his own life or fight to the death. With compassion, all words and tone of voice of the negotiators must be enlisted to persuade the surrounded perpetrator that to surrender peacefully is in his best interest.

Non-threatening proposals are methodically patient and respectful. Intimidating through threat has the swift kick of impatient fear. Males trapped as victimizing villains have to know their safety is assured by surrender. If all they will ultimately face is the Federal Death Penalty and certain execution, then murder/suicide will always be preferred. Underlying the entire nonviolent method of negotiation is the rejection of one-sided blame, using fear- driven ultimatums and threats.

We nonviolent practitioners reject this airtight case of blame which keeps us trapped in self-righteousness (

I am

not to blame); hooked on bitterness at what

they have done and conditioned use of revenge that will stop

them and teach

them (everyone?) a lesson. These are all life-threatening directions and won’t easily convince the violent person to cease being a threat or surrender

I have witnessed a team of police subdue and capture and individual who had crashed his car near our community driveway in the middle of the night. Dave, who was an intern with us, woke us at 2 am, to tell us of a seemingly drunk man who was moaning and walking behind the main house. We could not locate him after an extensive search of the woods. I called 911 to see if the police would help find him. My concern was that he was injured or unconscious. Five police arrived with dogs. They found him instantly, but that wasn’t enough. Guns had to be drawn; police screamed profanities and threats to immediately subdue the intruder. I learned an important lesson in relying on police tactics. The spirit of these methods of attack against dangerous people, usually in trauma, rarely yields a peaceful outcome. Because the nonviolent mediator is not fixed on the guilt of the wrongdoer, he/she is freed up emotionally to concentrate skillfully on their state of mind. The dialogue is more concerned with quieting their aggression and panic, than in threatening them with violent consequences and tough talk.

Disarming ourselves is the key to the method here, using words and that persuade: “We do not want to hurt you.” Resolutions from respectful dialogue with the fugitive take more time than screaming, shooting, subduing and killing. But, agreements made in trust are more reliable and lasting than twisting arms until fugitives give up and much safer for all parties concerned as well.

Another lesson I learned from Eastern Philosophy and Religion is in effect: “When someone makes me suffer unjustly, I don’t demonize or retaliate. I look within.” Now, what would I find if I looked within? Probably, an intense fear and resentment of the “enemy” who has hurt me. Behind that fear is another one—a morbid fear of suffering and death. Again, my own well-being is best protected, not with revenge, but with concern for the life of this “dangerous fugitive.” If my own fear is under manageable control, my compassion for both myself and the perpetrator can now operate effectively.

I have enough emotional freedom to cultivate sympathy for this “killer.” The person in charge of the negotiation might wonder what is driving his madness and his desire to maim or kill. Dzhokhar’s life had been surrounded by men (and likely a mother) who promoted using weapons and violence for their own ends and now we learn that he was apparently under the violent spell of his older brother. Psychologists speculate that because Dzhokhar’s father left him to return to Russia at 16 that Tamerlan could likely have become the “not to be questioned father.” Good crisis negotiation honors that humans can frequently behave out of deep emotional scarring.

In the wellspring of compassionate listening and speaking, a resolution also comes from faith in a forgiving God. Were I more susceptible to the violence of my culture, more swayed by ethnic hatreds, were I more brainwashed by an older brother’s religious delusions and hatreds, I too might be driven to the same unthinkable acts. And yes, “I am my brother’s keeper, even when he is murdering.” I must confess, “There but by the grace of God go I.”

Yes, I am to love this “enemy” and to help him heal his murderous delusions and hatreds. Yes, nonviolent healing love is God’s love and yes, it may risk my life, but it is the same risk those first (nonprofessional and professional) responders made by running toward the danger to themselves to rescue the injured and to save, not their own lives but the

lives of others, at the Boston Marathon.

The most important conclusion? It is possible to disarm and heal lethal passions with nonviolent compassion. Indeed it is the

only true way.